Richard Schweitzer

Postdoc in Vision Science

Centro Interdipartimentale di Mente e Cervello / Università di Trento

Richard Schweitzer is a vision scientist with a focus on computational models of the visual system which are empirically grounded in experiments using combinations of human psychophysics, eye and motion tracking, and M/EEG. He is currently postdoc at the Centro Interdipartimentale Mente/Cervello where he works with Christoph Huber-Huber on the potential link between active vision and hippocampal mechanisms.

During his PhD in Martin Rolfs' lab, he investigated the extent and the potential function of intra-saccadic vision. As a postdoc at the Berlin-based cluster of excellence Science of Intelligence he worked on the mechanisms underlying visual stability, not only in humans, but also in (custom-built) robots.

In his work he is passionate about applying novel technologies and experimental paradigms, building unique models and research equipment, developing useful and publicly available methods and algorithms, and contributing to Open Science. He has more than 10 years of experience in experimental research, programming, data analysis and statistics, scientific communication and writing, supervision and teaching.

- Vision around and during eye movements

- Sensorimotor control and learning

- Visual stability

- Computational modeling

- Research methods

- Time perception

-

Dr. rer. nat. Experimental Psychology, 2020

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin / Western Sydney University

-

M.Sc. Mind and Brain, 2016

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin / Bar-Ilan University

-

B.Sc. Psychology, 2013

Universität Potsdam / Università degli studi di Milano-Bicocca

Research

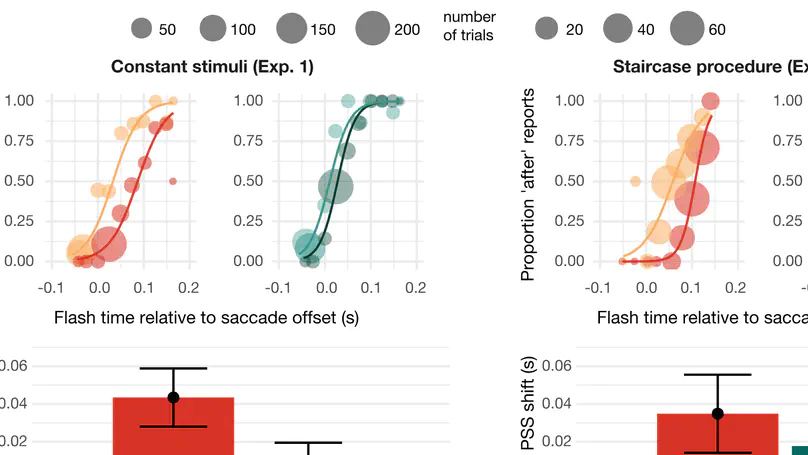

Temporal recalibration is a fascinating phenomenon. If one (experimentally) induces a consistent artificial delay between an action (e.g., pressing a button) and a visual stimulus (e.g., the light turning on), then - after a few exposures - stimuli occuring at shorter delays may well appear as if they happened even before the action was executed. In this piece Wiebke shows temporal recalibration across a good range of visual conditions with not only real but also simulated saccades.

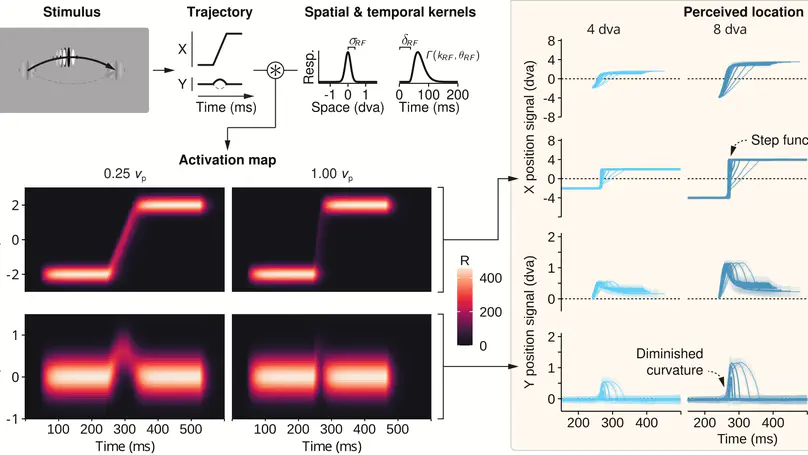

To efficiently explore our visual environment, we humans incessantly make brief and rapid eye movements. These so-called saccades inevitably shift the entire visual image across the retina, thereby inducing - like a moving camera with long exposure duration - a significant amount of motion blur, transforming single objects into elongated smeared motion streaks. While simultaneously recording electroencephalography and eye tracking, we asked human observers to make saccades to a target stimulus which then rapidly changed location while their eyes were in mid-flight. Critically, we compared smooth target motion to a simple jump, thus isolating neural responses and behavioral benefits specific to motion streaks. For continuous motion (i.e., when streaks were available), the post-saccadic target location could be decoded earlier from electrophysiological data and secondary saccades went more quickly to the new target location. Indeed, decoding of target location succeeded immediately after the end of the saccade and was most efficient on occipital sensors, suggesting that saccade-induced motion streaks are represented in visual cortex. Computational modeling of saccades as a consequence of early visual processes suggests that fast motion could be efficiently coded in orientation-selective channels, providing a parsimonious mechanism by which the brain exploits motion streaks for goal-directed behavior.

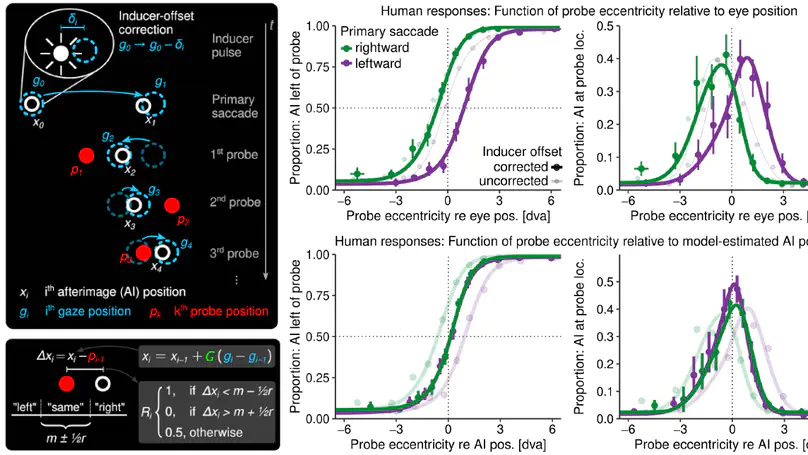

In low-light environments, brief high-intensity visual stimulation can induce long-lasting retinal afterimages. When observers then make eye movements to explore their visual environment, these afterimages – albeit fixed in the retinotopic frame of reference – appear to move in egocentric space wherever the eye moves. Even though this phenomenon has been known for centuries, the underlying computations remained unexplained. Tracking eye and afterimage positions simultaneously, we found that perceived afterimage position was accurately predicted by eye position across a variety of visuomotor conditions, whereby the eye movement’s size was however systematically underestimated by the visual system. Considering a parsimonious model of visual localization, afterimage movement can be understood as a consequence of feedforward predictions of the visual consequences of impending eye movements.

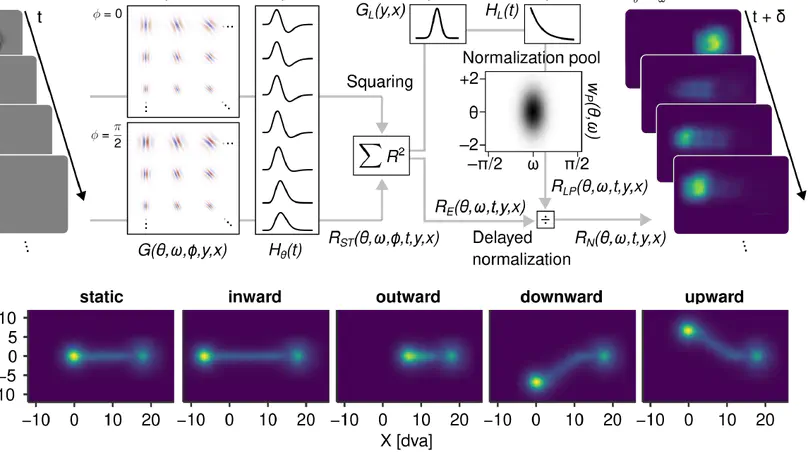

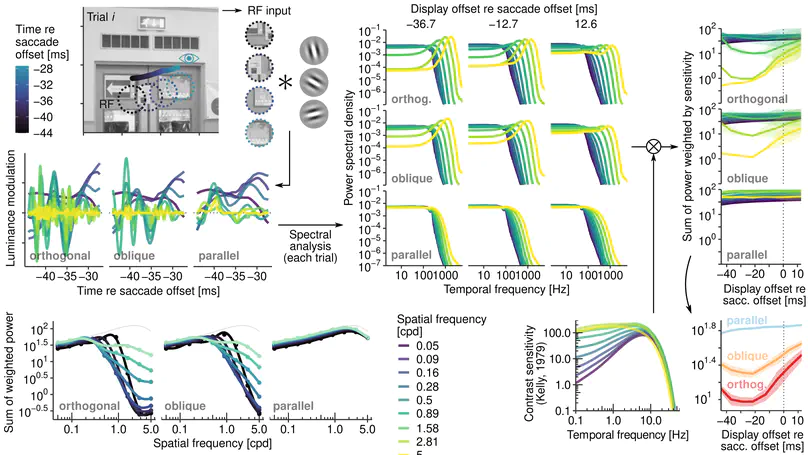

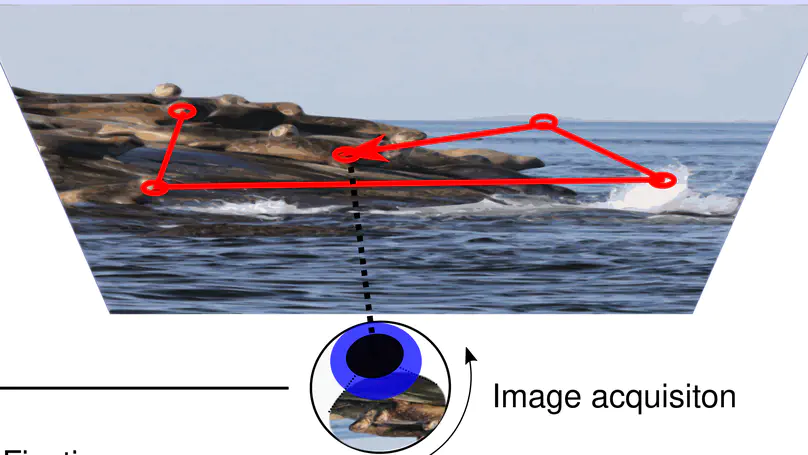

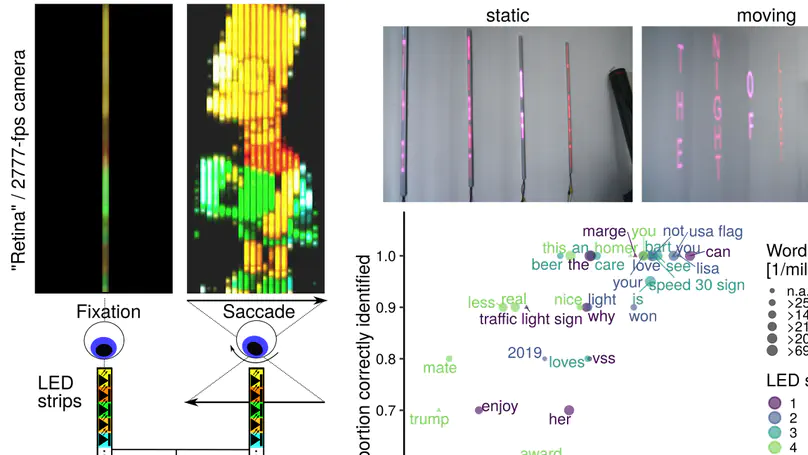

We rarely become aware of the immediate sensory consequences of our own saccades, that is, a massive amount of motion blur as the entire visual scene shifts across the retina. In this paper, we applied a novel tachistoscopic presentation technique to flash natural scenes in total darkness while observers made saccades. That way, motion smear induced by rapid image motion (otherwise omitted from perception) became readily observable. With this setup we could not only study the time course of motion smear generation and reduction, but also determine what visual features are encoded in smeared images. Low spatial frequencies and, most prominently, orientations parallel to the direction of the ongoing saccade. Using some cool computational modeling, we show that these results can be explained assuming no more than saccadic velocity and human contrast sensitivity profiles. To demonstrate that motion smear is directly linked to saccade dynamics, we show that the time course of perceived smear across observers can be predicted by a parsimonious motion-filter model that only takes the eyes’ trajectories as an input. And the best thing is that this works even if no saccades are made and the visual consequences of saccades are merely replayed to the fixating eye. In the name of open science, all modeling code, as well as data and data analysis code, is again publicly available.

In this paper, we report a mysterious finding. When detecting rapid stimulus motion of a Gabor stimulus oriented orthogonal to its motion direction, it is not simply its absolute velocity that determines its visibility, but a combination of velocity and movement distance. Curiously, the specific combination that predicts velocity thresholds follows an oculomotor law, that is, the main sequence, an exponential function describing the increase of saccadic velocity with growing amplitude. My proud contributions to this paper feature the masking experiment, the modeling of saccade trajectories which ultimately revealed significant correlations between saccade metrics and velocity thresholds, and most importantly, the early vision model to predict the measured psychophysical data, without fitting and based only on the trajectory of the stimulus. Finally, I evaluated the timing of the motion stimulus using photometric measurements using the LM03 lightmeter.

When looking at data recorded by video-based eye tracking systems, one might have noticed brief periods of instability around saccade offset. These so-called post-saccadic oscillations are caused by inertial forces that act on the elastic components of the eye, such as the iris or the lens, and can greatly distort estimates of saccade duration and peak velocity. In this paper, we describe and evaluate biophysically plausible models (for a demonstration, see the shiny app) that can not only approximate saccade trajectories observed in video-based eye tracking, but also extract the underlying – and otherwise unobservable – rotation of the eyeball. We further present detection algorithms for post-saccadic oscillations, which are made publicly available, and finally demonstrate how accurate models of saccade trajectory can be used to generate data and mathematically tractable ground-truth labels for training ML-based algorithms that are capable of accurately detecting post-saccadic oscillations.

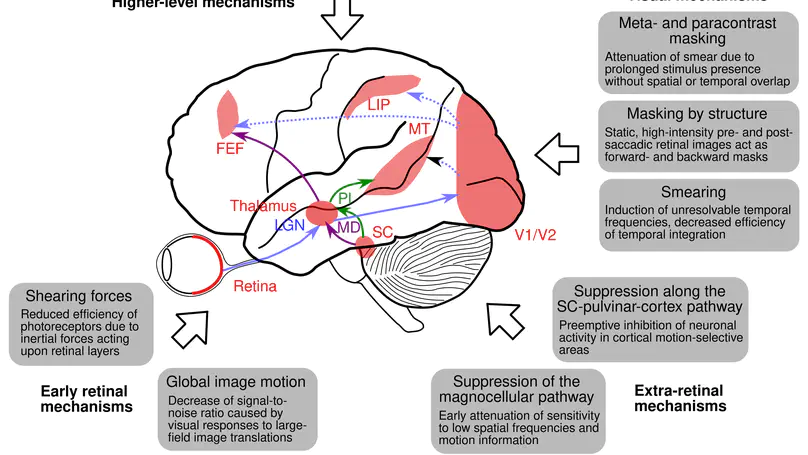

This perspective paper is dedicated to the question how an active perceptual system deals with the sensory consequences of its own actions. For instance, in the field of active vision little is known about the consequences of large-field smear induced by the rapid image shift caused by saccades. Whereas such information is thought to hinder visual processing, new evidence is discussed that sheds light on the intriguing possibility of action-perception couplings, that is, the idea that perception is shaped by sensory consequences of actions.

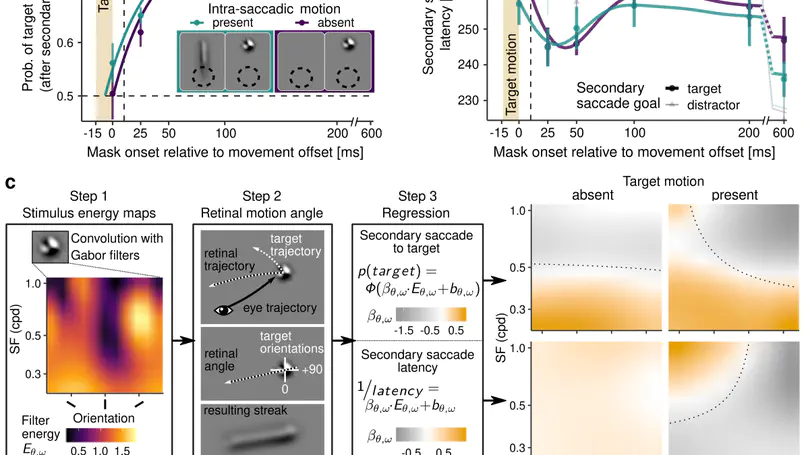

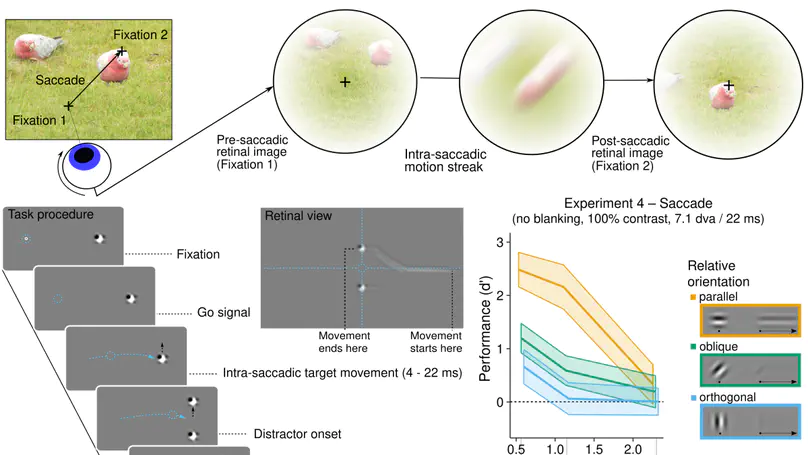

In this piece we showed that the visual traces that moving objects induce during saccades can facilitate secondary saccades in both accuracy and saccade initiation latency. Secondary saccades are typically prompted when one saccade does not entirely reach a target or when the saccade target is displaced in mid-flight. Our results provide evidence against the widely acknowledged notion that our brains preemptively discard visual information which reaches the eye during saccades. The paper has received some peer and media attention, such as a well-written commentary by Jasper Fabius and Stefan van der Stigchel, as well as articles in Nature Research Highlights, AAAS, New Scientist, or Vozpópuli (see the Rolfslab's blog post for the full list). Notably, this study is the first one to apply the new TrackPixx eye tracking system, for which I have written a Matlab toolbox.

Is intra-saccadic vision merely an epiphenomenon or could visual information that reaches the eye during saccades be used by the visual system? That was the question of my cumulative doctoral dissertation, which features not only a synopsis of all studies conducted up to this point, but also a review of the saccadic-suppression and motion-streak literature to put these findings into context. The dissertation has been awarded two prizes – the Humboldt Prize and the Lieselotte Pongratz-Promotionspreis by Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes (see also the short movie).

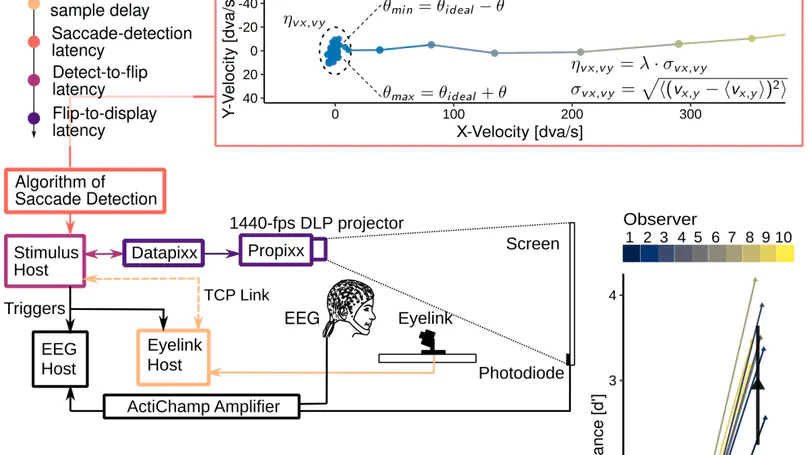

Whenever we make a saccade to an object, that object will travel from the periphery to the fovea at extremely high velocities. Depending on the visual features of the object, such motion can induce streaks, that may serve as visual clues to solve the problem of trans-saccadic object correspondence. Using a high-speed projection system operating at 1440 fps, we investigated to what extent human observers are capable of matching pre- and post-saccadic object locations when their only cue was an intra-saccadic motion streak, and compared their performance during saccades to a replay of the retinal stimulus trajectory presented during fixation. Note that a toolbox for parsing Eyelink EDF files was implemented in R to analyze this series of experiments, which can be found here.

To study intrasaccadic vision, we need stimulus manipulations that occur strictly during saccades. Due to the brief durations of saccades, this can prove a difficult task, as various system latencies (eye tracker, refresh cycle, video delay, and some more) have to be considered. While most of these delays are hardware-dependent, one opportunity to alleviate timing issues in gaze-contingent eye-tracking paradigms is applying an efficient online saccade detection! In this paper we described such an algorithm, validated it in simulations and experiments, and made it publicly available so that it can be used with a range of different programming languages.

Everyone knows this nice party trick – try to observe your own rapid eye movements (so-called saccades) in the mirror and realize that you will not be able to. Despite this striking example, we are not blind during saccades. This paper features a demonstration (as well as schematics and code to built it yourself) that is capable of producing highly salient, nicely resolvable stimuli which can only be perceived during saccades!

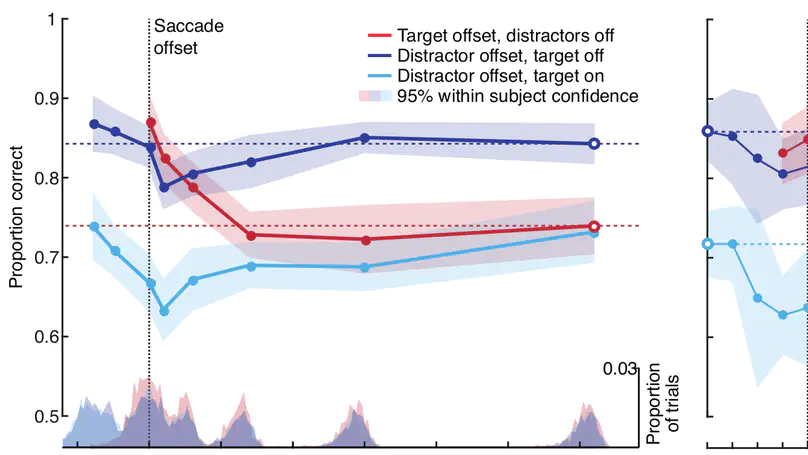

When objects rapidly shift across the retina during saccades, they produce so-called motion streaks – elongated traces of the stimulus trajectory. During natural vision, however, we rarely notice this type of smearing. Previous studies have shown that the mere presence of stimulus after the saccade can achieve this ‘saccadic omission’. Tarryn’s study investigates not only the time course of this process but also the unexpected role of distractor stimuli. She has written a nice piece on her work for Science Trends.

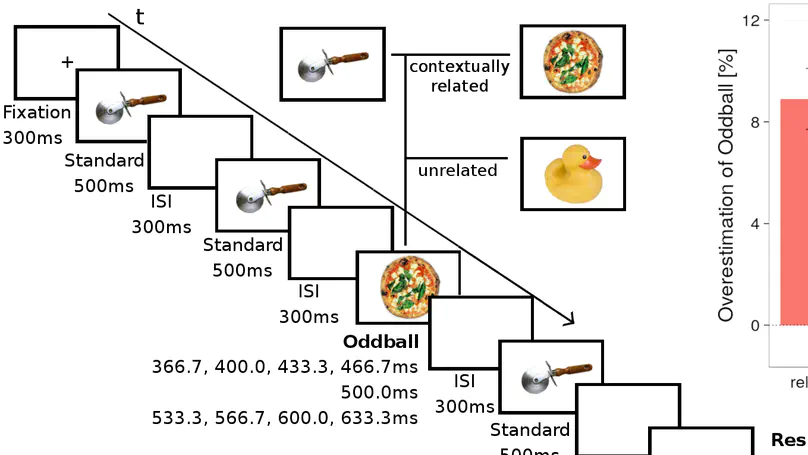

The temporal oddball effect – that is, the phenomenon that the duration of an oddball stimulus is overestimated when compared to the duration of a standard stimulus which is repeatedly presented in a stream – is thought to be driven by prediction errors. Suprisingly, and in contrast to this predominant hypothesis, we found that a more predictable oddball object (e.g., a pizza following a pizza cutter) is overestimated to a larger degree than a fully unpredictable oddball (e.g., a rubber duck following a pizza cutter). How could this be explained?

Publications

Feel free to contact me in case the access to any of these publications is restricted.

Contact

- richard.schweitzer@unitn.it

- Palazzo Fedrigotti, Corso Bettini 31, Rovereto (TN), 38068